Have you ever gone through a drive-thru lane at a bank and seen that tube system that rockets a deposit from the car to the teller inside? Pretty awesome stuff, huh? That is a pneumatic tube. Pneumatic describes something operated by air under pressure. That bank tube uses compressed air or a vacuum to move that little cylinder holding your money through that slightly larger diameter tube.

If you’re like us, you’ve probably wondered what it would like to be to ride in one of those little guys. As usual, history’s already been there.

If you’re like us, you’ve probably wondered what it would like to be to ride in one of those little guys. As usual, history’s already been there.

In 1870, long before a subway system would be successfully installed in New York City (or any other American city), a man named Alfred Ely Beach had an idea. He knew about a few pneumatic tube systems in England used to transport notes

and small packages, but he had the big idea to make one large enough to comfortably move a group of people.

You see, New York was getting crowded and people were looking for a way to move large groups quickly, safely, and easily. If they can be moved somewhere besides the already crowded streets: even better. Some people suggested elevated train tracks with cars pulled by horses. But large animals above the street had some drawbacks. A big one is falling manure. Gross.

Steam powered engines were suggested too, but many people were weary of the dangers of these exploding near crowds, which had happened before.

The idea of creating a system underground wasn’t unheard of, but many people were scared. The thought of city blocks collapsing when the earth beneath them was removed to build tunnels was terrifying. Alfred Beach believed it could be done, though. He also knew he would have a hard time getting the proper permissions for his experimental subway, so when he

approached the city government, he told them he would be building a smaller tube system, to send mail to the post office.

Being as that it was an experiment, and a secret one at that, he would start small: just about as long as a city block. In a sense, it was a classic case of believing “sometimes it’s better to beg for forgiveness than to ask for permission.” But Beach didn’t see himself begging for forgiveness; he saw his creation changing the city for the better. He just had to prove it.

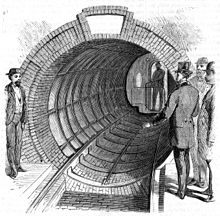

So his team started digging. And digging. And digging. The men dug a tunnel that was 300 feet long and ran along Warren Street, before making a curve along Broadway. The tunnel would have a diameter of 8 feet and was lined with bricks painted white.

Meanwhile, another team was working on the passenger car. It was a lot like that cylinder for money at the bank, except on the inside it was plush, with comfortable couches that could easily seat eighteen people. It featured fancy wood paneling and, because it was underground, new zirconia lights, a chemical lighting that was used before electric bulbs. Yet another team installed a giant Indiana-built fan at one end of the tunnel.

Fifty-eight days after starting, on February 26, 1870, it was done. People had heard the construction and knew something unusual was happening, but when they walked in to the beautiful salon-like waiting room they were flabbergasted. Beautiful paintings, lamps, a goldfish pond, and even a pianist playing a grand piano awaited them when they descended below the busy streets above. Rides were twenty-five cents, and the proceeds benefited the Union Home for Orphans of Soldiers and Sailors.

Basically, it worked like this: Once the car was loaded, and the doors shut, the giant fan would blow the car along a track thru the tube. When it was time to head back the other direction (it was only 300 feet long), the fan was reversed, creating suction, or a vacuum in the tube. This would draw the passenger car back to the original location.

People loved it. Yet, brilliant as it may have been, it didn’t last long. For a few years it was operated as a demonstration. Beach wanted to create an entire system like this one over much of the city, making it easy for people to move quickly without creating traffic jams. Funding was tough, especially after the stock market crash. Furthermore, other people with much more influence than Beach, pushed other ideas and the city decided to build an elevated train system instead.

It wasn’t until 1912 that the modern New York Subway system was begun, albeit with more familiar means of locomotion. Now millions of people travel underneath cities all over the world every single day. Beach was a pioneer in this manner.

His pneumatic system still did amount to something in New York City. Though Beach’s tunnel is long gone, his idea for pneumatic mail movement eventually happened in the city. From 1897 to 1953, pneumatic tubes carried mail all over the city, including the four-minute zip from Brooklyn to Manhattan.

Leave a Reply